Overnight temperatures in the workshop are slowly rising toward the minimum needed for epoxy work (for boat building). Spring might be coming. Song birds are returning their joy to the neighborhood. Boy are those babies getting a surprise today. We have 12-18 inches of crystalline global warming falling from the skies today and tomorrow. So, work continues on the treadle lathe.

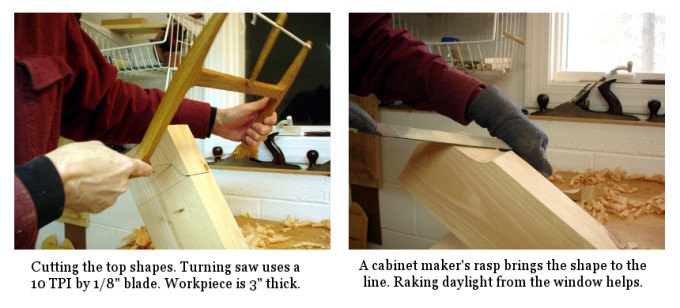

When I was making the flywheel, I doubted the ability of my trusty turning saw to do a good job with the wheel’s thick stock. I wimped out and used the bandsaw to ensure a round wheel. Wanting ogee curves on the tops of the headstock and tailstock posts, I decided to give the turning saw a try. These posts are the same thickness as the wheel.

The only difference between these cuts and the wheel was the level of perfection needed. It turns out that the saw, using the 10 TPI 1/8″ Gramercy blade, acquitted itself quite well.

On a piece of cardboard carton (empty pasta box) I drew a curve that pleased me. I traced around that to position the pattern on both sides of all three of the parts. Sawing close to the line was not at all difficult. Yes, it was slow going but cost only a couple of Milky Way bars. A Nicholson 2nd cut cabinetmaker’s rasp was my tool of choice for completing the shaping.

Boatbuilders often use beading to dress up the plain parts of small boats, usually the thwarts. The beading shows good craftsmanship and also eases the comfort of bare legs sitting on the thwarts. Stephen Shepherd recommended beading in his lathe bench plan notes. So, I want to use beading on some of the parts.

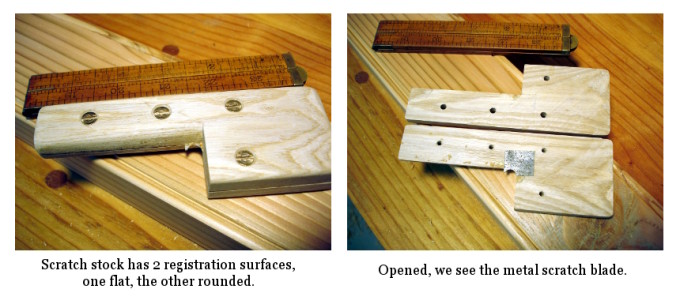

Having never done it, I researched (of course), and determined a scratch stock is the tool of choice for such work. More research found me many ways of building a scratch stock tool. I ended up eliminating all but two, a design by Tom Casper in the October 1999 issue of American Woodworker (a bunch of them online thanks to Google Books), and a design by our beloved Village Carpenter, Kari Hultman.

As much as I like the simplicity of Kari’s approach, I thought the design with two reference surfaces would be easier to control. I made it from a bit of Ash. The basic “L” shape was cut first.

Then, I fitted the screws, removed them, and resawed the tool into two pieces. Rounding the long fence face, and rounding over all the other edges completed the stock. The scratch blade is a bit of saw blade cut to a small square and then filed with a rattail file.

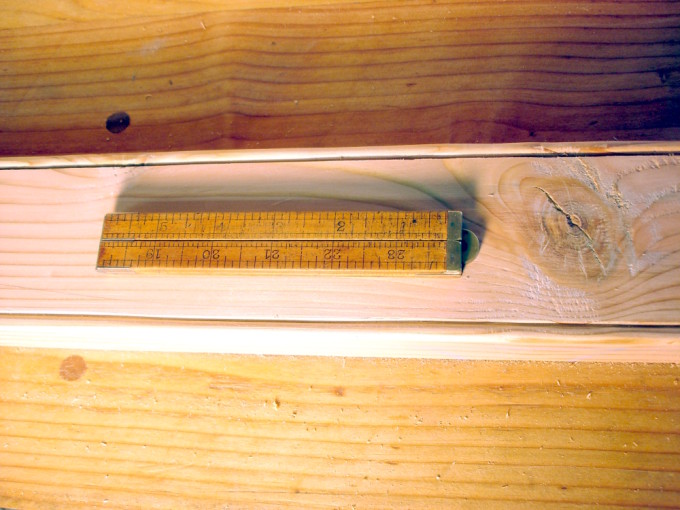

It works surprisingly well. It’s a good way to improve the appearance of this marginally acceptable lumber. Now, the real reason for beading is to strengthen the part. A piece of lumber with sharp square edges is subject to splintering as it transitions through humidity changes. Splintering leads to splitting. Splitting leads to twisting and warping. Knocking off the sharp square edge significantly lessens the potential for splintering and all the rest. Hence, strengthening the piece, while making it more attractive.

Roy’s spring pole lathe is on my list of shop projects. I’m curious to try the reciprocating action vs. continuous rotation. The bodger-in-the-woods aspect also appeals to me.

I’m glad to see the Gramercy turning blade working well. In addition to the Hyperkitten framesaw I’ve had half-built for over a year, and bandsaw blades for Drew Langsner’s turning saw, I got the parts for the Gramercy saw recently.

The issue l see with making these yreadle lathes according to the plans provided is that they were designed for someone else of a different body size/height. The most important thing is that the centers should be tha same heignt as your elbow. Lower, as is usually the case, and it will cause strain on your lower back and not a little discomfort. Too high and it restricts your range of motion. This principle applies to all types of lathes used for hand turning.

Which is why I use plans as a GUIDE, not for exact measurements. I built the lathe the right height for me. As with any project, plans are guides, not absolutes.