The one point of agreement in the many plans I’ve collected is having a flywheel of 24 inch diameter.

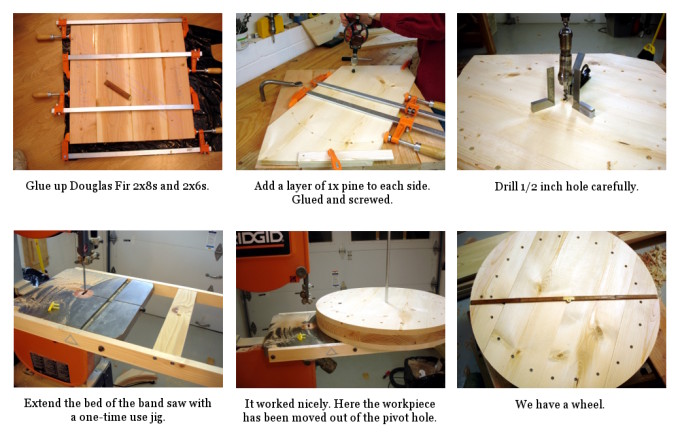

Construction varies with the different plans, some with interesting spokes and rims, some solid. I chose solid: easy. I like easy. It wants to be a substantial wheel, the heavier the better. Two layers of 2-by lumber would do it. However, that would leave a seam in the middle of the wheel. What if I decide to drive it with a cord rather than a flat belt. Wouldn’t that seam invite trouble as a gutter is routed for the cord? To avoid that eventuality, I used 2-by material for a middle layer, and then attached 1-by material on either side. Yellow carpenter’s glue and a bunch of countersunk screws bring the layers together, each offset by 60 degrees.

Now, let’s make it round. I really really really like doing as much as possible with hand tools. I have a great turning saw that uses Gramercy blades. However, this wheel presents 3 problems. First, the coarsest Gramercy blade is 10 TPI and 1/8 inch wide. That seems a bit skimpy for this cut. I would prefer 6-8 TPI and 1/4 inch wide, a size not available. Second, a wheel really needs to be round with a nicely perpendicular edge, something I imagined hard to achieve by hand. Third, I don’t have enough Snickers bars on hand to power that much sawing.

So, it’s time to dust off the band saw … and extend its table. It didn’t take much to knock together a one-time use table extension that has a pivot hole 12 inches from the blade. It took longer to find the screws than to make the extension. The table on this Rigid saw has holes tapped for 6mm by 16 screws. How many of you can find 4 of those in your loose parts collection? I did. 🙂

There it is, a simple wheel. It weighs 24 pounds. I don’t know if that is heavy enough.

Oh, before I quit, let me show you one very sweet hand drill bit. I learned from my fellow galoots over at the Saw Mill Creek forums that it might be a Cook (US patent) or Gedge (UK patent) pattern. Most of the hand drill bits we see these days are either Russel Jennings or Irwins, with spurs pointing toward the tip. This bit has the spurs turned back toward the shank. It makes a very easy entry, and better yet makes a very clean exit. There’s no tearout at the exit; no need to stop before exiting and drill back from the other side. It seems that Ransom Cook patented this pattern a few weeks before Jennings, but maybe didn’t have as good a marketing department. The Jennings bits prevailed.

Chasing another of the patent references made by Jeff in the forums, I see a patent by James Swan, some 20 years after Cook’s. Swan’s improvment was to extend the cutting edge from out at the curl all the way into the screw. My bit is indeed a Swan. This one came to me as one of a handful of odd bits that Patrick Leach threw in the box when I bought the Stanley brace. It’s the only one of that pattern I have. After using it, I’m wanting more.